In the sweltering summer of 2021, five Chinese scientists ignited a firestorm of intrigue when they unveiled a startling discovery: a remarkably preserved skull, dug from the earth of northeastern China, belonging—so they claimed—to a new kind of human. They named it Homo longi, or “Dragon Man,” after the Dragon River region where it was found.

But beneath that fossilized brow, buried deep in the bone and tooth, lay a far greater secret. One that would take years, and a scientific sleuth, to uncover.

Enter Qiaomei Fu, a paleogeneticist with a quiet demeanor and a history-making résumé. In 2010, she helped sequence ancient DNA from a tiny pinkie bone in a Siberian cave called Denisova. That fragment changed everything: it revealed the Denisovans, a mysterious branch of humans no one had ever seen—until now.

When Fu saw the Dragon Man skull, she had a hunch: Could this be the face of the Denisovans?

The Hunt for Ancient DNA

Fu asked for access. The answer was yes. Her target: DNA hidden deep in the skull’s fortress-like structure—specifically the teeth and the dense petrous bone near the ear, where genetic material can cling for millennia. But even these yielded nothing.

Refusing to give up, Fu switched tactics. She turned to proteins—less delicate than DNA, and still capable of telling the story of genes long degraded. She extracted 95 different proteins, four of which are known to differ between Denisovans and other hominins. In three of those four, the Harbin skull carried the Denisovan variant.

But that wasn’t enough for Fu. She needed DNA.

And so, she searched the last, most unlikely refuge: the crusted dental plaque on Dragon Man’s lone remaining tooth. It was a shot in the dark. But against all odds, she struck gold.

Hidden in the hardened grime of ancient breath, Fu found a sliver of human DNA. It was old. Too old to be contamination. And—crucially—it matched genetic markers found only in the seven known Denisovan individuals. Twenty-seven gene variants. None found in modern humans.

As Fu put it: “After 15 years, we give the Denisovan a face.”

The Skull That Speaks

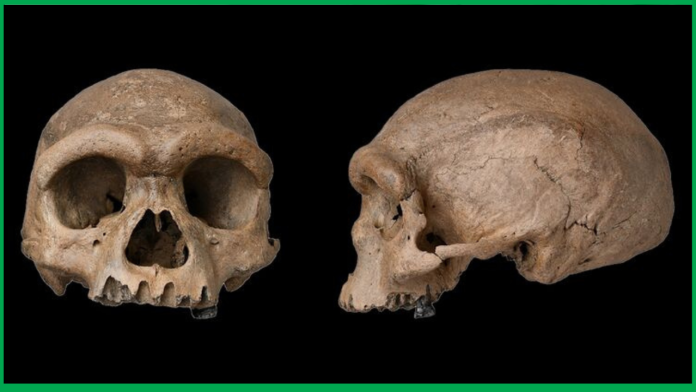

The skull, now known as the Harbin cranium, is unlike anything we’ve seen. It is huge—suggesting a human with a powerful build, capable of withstanding the ice-bitten winters of ancient China. Its face is wide and low. A heavy brow ridge juts forward, yet its cheekbones are delicate. The lower face is flatter, more modern—far from the jutting jaws of apes and archaic hominins.

This was no brute. It was something in between.

Now, for the first time, scientists can match a complete human face to the elusive genetic ghost known only from cave dust and bone shards. A people long invisible in the fossil record have taken human form.

“This is big,” says University of Toronto paleoanthropologist Bence Viola, who wasn’t part of the study but has worked at Denisova Cave. “We might finally understand how these humans adapted to their world—how their bodies, their brains, their lives evolved in the cold shadows of the Ice Age.”

The Debate Over Names

Yet with discovery comes controversy.

If this skull is a Denisovan, and if Homo longi is now genetically tied to Denisovans, should we rename the entire group? Should Denisovans become Homo longi?

Some, like paleontologist Xijun Ni, say yes. “It’s like calling both New Yorkers and Beijingers Homo sapiens. Denisovans were a population within Homo longi.”

Others disagree. Svante Pääbo, the Nobel Prize-winning pioneer of ancient DNA, warns against labeling Denisovans a separate species at all. After all, they had children with Neanderthals—and with our own ancestors. “They mixed,” he says, “they were family.”

From a Cave in Siberia to the Heart of East Asia

For years, the Denisovans were a mystery wrapped in darkness. Their entire existence hung on a finger, a few teeth, and ancient DNA scraped from the dirt. Now, suddenly, we have a face. A skull. A life-size glimpse into a lost chapter of our human story.

And that story stretches far wider than we thought.

The Harbin skull proves Denisovans didn’t just haunt the Siberian mountains. They ranged across East Asia, maybe further. Their bones may lie beneath the soils of China, Laos, and Tibet. Their descendants still whisper in our genes—especially among Indigenous populations of Southeast Asia and Oceania.

And this skull may be the key to unlocking all the other mysterious fossils scattered across the continent—bones we couldn’t classify, faces we couldn’t place. Until now.

A Final Clue in Ancient Plaque

It’s almost poetic: after years of digging through caves, bones, and theories, the confirmation of one of humanity’s greatest mysteries came not from a grand new find—but from the gnarled plaque of a long-dead tooth.

Fu knew it was a long shot. She even jokes that much of the DNA they first recovered likely came from her. “I studied and handled the skull so many times,” she laughs. But deep within the plaque was a fragment—real, ancient, true. It belonged to Dragon Man. And it belonged to the Denisovans.

A Pinkie Bone Gave Us a Mystery. Now, We Have a Face.

The Denisovans were once shadows. Now they have substance. A massive skull. A broad face. A towering figure who once walked the frozen rivers of China.

We still don’t know everything—how they lived, why they vanished, or how much of them remains within us. But one thing is now certain:

The ghost species is a ghost no more.