Hurricanes are among the most powerful forces on Earth, combining intense winds and torrential rain into devastating storms. When they strike land, their high-speed winds can tear apart buildings and even spawn tornadoes. But often, the deadliest part isn’t the wind—it’s the rain. The flooding that follows can be catastrophic and lethal.

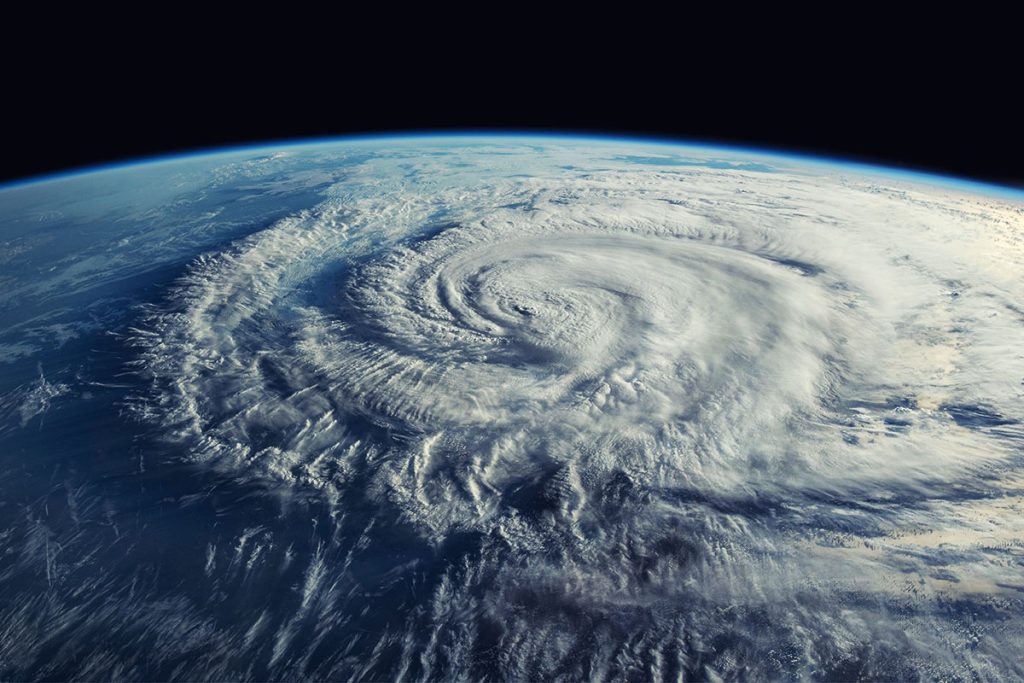

These monstrous storms are fueled by warm ocean water and rotate in a distinctive spiral shape. They begin as tropical storms, earning a name once sustained winds reach 39 miles per hour. Once those winds exceed 74 miles per hour, the storm is officially classified as a hurricane. The strength of a hurricane is measured using the Saffir-Simpson scale, which ranks them from Category 1 (least severe) to Category 5 (most extreme).

Though similar in structure, these storms go by different names depending on where they form:

- Hurricanes occur in the North Atlantic, central and eastern North Pacific.

- Typhoons develop in the Northwest Pacific.

- Cyclones form in the South Pacific and Indian Ocean.

But what exactly causes hurricanes to form—and how can we stay safe when they do?

How Hurricanes Form

Centuries ago, European explorers borrowed the word hurakan from Indigenous Caribbean cultures to describe the violent storms that wrecked their ships. Today, we know much more about how hurricanes form and behave.

In the Atlantic, hurricane season peaks from mid-August to late October, typically producing five to six hurricanes a year. In the northern Indian Ocean, cyclones tend to form between April and December, peaking in May and November.

Hurricanes start as clusters of thunderstorms over warm ocean water—at least 80°F (27°C) at the surface. These areas of low pressure act like massive engines, drawing in warm, moist air that rises and cools, releasing energy through condensation. This process intensifies the storm.

As the storm strengthens, it develops a well-defined center known as the eye—a calm zone roughly 20 to 40 miles wide. Surrounding the eye is the eyewall, a ring of intense winds and heavy rain. This is where the storm is most dangerous.

Why Hurricanes Are So Dangerous

When hurricanes hit land, they can unleash a range of destructive forces:

- Storm Surge: Powerful winds push ocean water onto the shore, creating surges that can reach up to 20 feet (6 meters) high and travel miles inland.

- Flooding: Heavy rains can lead to flash floods and landslides—sometimes far from the coast.

- Wind Damage: High winds can level homes, uproot trees, and knock out power for days or even weeks.

- Tornadoes: Hurricanes can spawn tornadoes, adding another layer of danger.

Storm surges and flooding are especially deadly—responsible for about 75% of deaths from Atlantic tropical cyclones, according to a 2014 study. Hurricane Katrina in 2005 killed more than 1,200 people, with a third of deaths caused by drowning. It remains the costliest hurricane in U.S. history, with $125 billion in damages.

Although Atlantic hurricanes are powerful, the strongest storms often form in the Pacific, where there’s more open water to fuel their growth. In 2015, Hurricane Patricia reached record-setting winds of 215 mph off the coast of Guatemala. The most powerful Atlantic storm, Hurricane Wilma in 2005, had winds of 183 mph.

The key to survival? Early warnings. Agencies like the U.S. National Hurricane Center issue:

- Hurricane watches when a storm could hit within 48 hours.

- Hurricane warnings when a strike is expected within 36 hours.

Climate Change and Hurricanes

As the climate warms, hurricanes are becoming stronger, wetter, and more unpredictable.

In 2018, the world saw a record 22 major hurricanes in under three months. In 2020, the Atlantic season produced a staggering 30 named storms—14 of them hurricanes, with seven reaching major status.

What’s driving this trend? Warmer oceans and air.

- Hotter water provides more fuel for storm formation and intensification.

- Warmer air holds more moisture, resulting in heavier rainfall.

- Rising sea levels make storm surges even more dangerous.

- Slower-moving storms—another climate-linked trend—can linger over one area, dumping more rain and increasing damage.

Take Hurricane Harvey in 2017, for example. Fueled by Gulf of Mexico waters that were 2°F warmer than average, Harvey dropped a U.S. record 51.8 inches of rain on Texas.

Looking ahead, scientists warn that Arctic warming may shift storm tracks further west, making U.S. landfalls more likely. That’s why hurricane preparedness and addressing climate change aren’t just good ideas—they’re essential.

In Summary

Hurricanes are vast, complex storms driven by heat and moisture, capable of reshaping coastlines and devastating communities. While we can’t prevent them, understanding their formation, behavior, and increasing intensity can help us prepare, adapt—and survive.