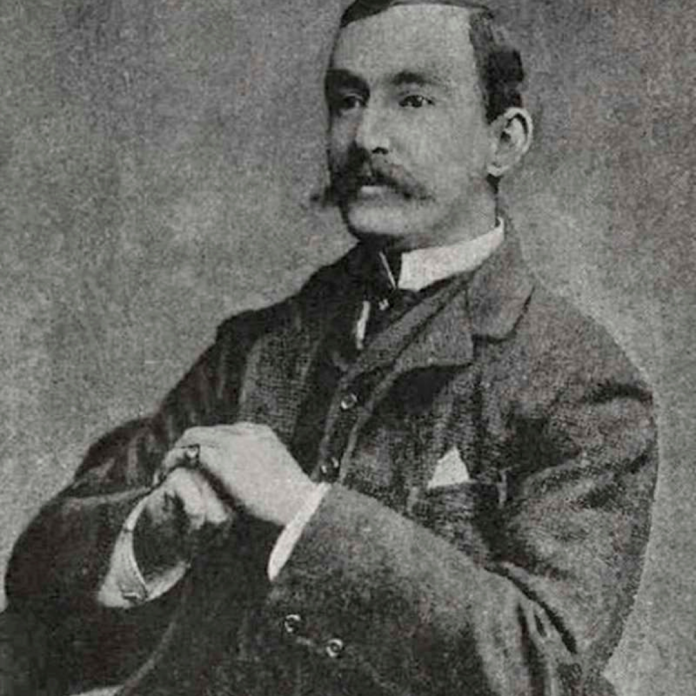

Last month, Guinness celebrated the memory of their founding father, Arthur Guinness, with fanfare. It made me think of another towering figure from a great alcohol dynasty—James Sligo Jameson, grandson of the man whose signature still graces every bottle of Jameson whiskey.

Jameson was the only Irish officer on Henry Morton Stanley’s doomed 1887 Congo River expedition, the first to push deep into Africa’s heart. In 1990, I followed parts of that same route and brought along Jameson’s diaries. Strangely, our experiences mirrored each other in unsettling ways. We each paid £1,000 to a British company for our journey, and each found ourselves wholly unprepared for the realities we would face.

Jameson wrote, “The last six months have been the most miserable and useless I have ever spent anywhere. Ever since my childhood, I have dreamt of doing some good in this world, and making a name which was more than an idle one.”

Both of us left Africa with remorse. In my book Truck Fever, I confessed to buying up food supplies in starving villages. Jameson, with disturbing honesty, recounts leading a brutal forced march: “One of the most disgusting pieces of work I have ever had to do. A lot of slave drivers of the old school would have done it much better, for that—slave-driving—is what it often resolved itself into.”

Africa, in its eerie symmetry, took its revenge on both of us at nearly the same place. Jameson and I were abandoned on the Congo River just three kilometres and 103 years apart. Both of us fell ill, starved, and were forced to act in ways we’d rather forget.

But what happened to Jameson goes far beyond the realm of forgivable mistakes. It’s a story so repugnant that Jameson Irish Whiskey will likely never raise a glass in his honour.

According to reports, Jameson, during a discussion about cannibalism with a local chief, offered six white handkerchiefs to see someone killed and eaten—allegedly for the sake of a sketch. In a letter to his wife, he claimed it was a misunderstanding:

“I sent my boy for six handkerchiefs, thinking it was all a joke… but presently a man appeared, leading a young girl of about 10 years old by the hand, and then I witnessed the most horribly sickening sight I am ever likely to see in my life. He plunged a knife quickly into her breast twice, and she fell on her face… Three men then ran forward and began to cut up the body. Finally, her head was cut off and not a particle remained. The most extraordinary thing was that the girl never muttered a sound, nor struggled, until she fell.”

Jameson claimed he only began sketching after the dismemberment began. He tried to rationalize it—to document horror, perhaps. But before he could clear his name, the story reached The Times of London. He died of fever shortly after, his reputation in ruins.

I, too, have blood on my conscience from my time in Africa. I once stood by while young boys were beaten with the butt of a machine gun until they bled. It’s a memory that haunts me still.

So yes, I’ll raise a pint to Uncle Arthur like the rest. But when I do, I’ll follow it with a quiet chaser in memory of James Sligo Jameson—a man broken by a continent, by history, and perhaps, by himself.

By Iris Times