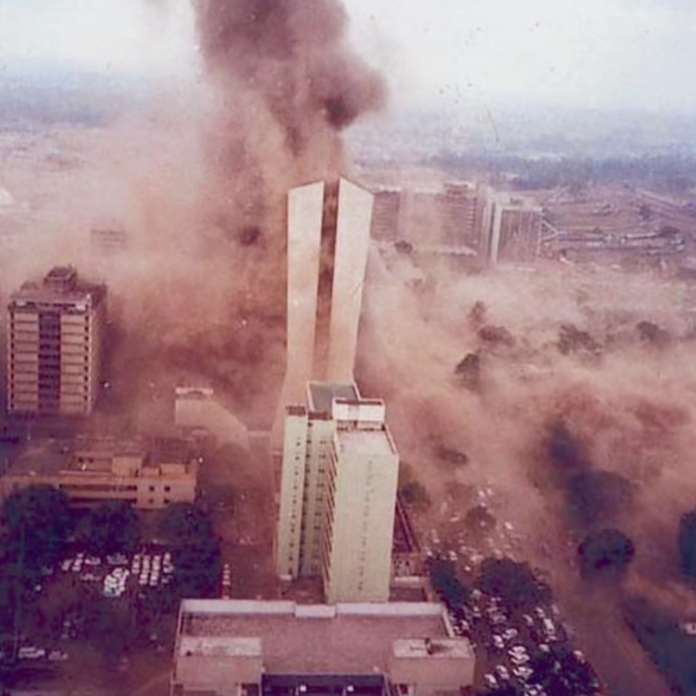

On August 7, 1998, nearly simultaneous bombs detonated at the U.S. embassies in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, killing 224 people—including 12 Americans—and injuring over 4,500 others. The scale and coordination of the attacks stunned the world and marked a critical turning point in the fight against terrorism. Yet, in the aftermath, troubling questions arose: Could this tragedy have been avoided? Were there signs that went unheeded, and what role did intelligence failures play in the bombings?

The FBI’s investigation, codenamed KENBOM and TANBOM, became one of the largest and most complex operations in Bureau history. Over 900 agents and countless global partners worked tirelessly to piece together the events leading to the bombing. Within weeks, the investigation pointed to al Qaeda, an emerging threat in the terrorism world. Yet the group’s growing presence had been largely under the radar for many intelligence agencies at the time, and even after the bombing, the links to bin Laden’s network were slow to materialize for some.

The bombings were not entirely unforeseen. In fact, there were growing signs of a mounting terrorist threat in East Africa. In the months before the attack, the U.S. government had been warned of al Qaeda’s intentions. In particular, a U.S. embassy bombing plot had been discussed in intercepted communications, but the intelligence was vague and lacked critical details. Despite this, the broader intelligence community did not act swiftly enough to thwart the plot. Many of the warning signs that could have disrupted the attack were either ignored or misinterpreted. A deeper look into the failure of cooperation between U.S. agencies, international partners, and inconsistent intelligence-sharing processes suggests there were missed opportunities to prevent the devastating events.

In the months leading up to the bombings, several intelligence sources indicated that something significant was brewing, but the information was fragmented. The CIA had knowledge of al Qaeda’s growing presence in the region, but there was no clear, actionable intelligence that could pinpoint the embassy targets. Despite increasing chatter around bin Laden’s operations and his stated desire to attack American interests, intelligence agencies were still piecing together the puzzle. Their inability to connect the dots highlights the systemic failures that allowed a well-organized terrorist network to carry out the bombings with minimal interference.

The FBI’s efforts, after the fact, were impressive, leading to the arrest and conviction of several key figures. Mohammed Sadeek Odeh and Mohammed Rashed Daoud al-Owhali were apprehended quickly, but their capture came only after the tragedy. Others, like Wadih el-Hage, were arrested for lying to federal investigators, and Mamdouh Mahmud Salim was apprehended in Germany, though his capture didn’t prevent the loss of life.

But the aftermath also revealed the flaws in intelligence sharing and collaboration. The U.S. intelligence agencies were often operating in silos, and crucial information wasn’t always shared in real-time between different agencies, creating gaps that hindered a coordinated response. The bombing exposed the limits of counterterrorism measures at the time and highlighted the need for an overhaul in how intelligence was handled.

The indictment of Osama bin Laden and key al Qaeda operatives was an important step, but the bombings served as a wake-up call that would resonate far beyond East Africa. The tragic event underscored the importance of preemptive action and the need for better intelligence-gathering and sharing to combat international terrorism.

Despite the subsequent efforts and arrests of over 20 individuals tied to the attacks, the question remains: Could the East African embassy bombings have been prevented with better intelligence? The failures of the intelligence community, and the lack of a coordinated global response, certainly suggest that much more could have been done to stop al Qaeda before it struck.

Ultimately, the bombings marked not just a tragic loss of life but a pivotal moment in how the U.S. and the world would view terrorism. They raised critical lessons about intelligence, the limitations of preemptive actions, and the ongoing challenges in addressing global terrorist networks. These lessons would set the stage for future counterterrorism efforts, but at a high cost.

By FBI